Our Vietnamese Project

Started in 2024, Dự án tiếng Việt (Our Vietnamese Project) is a collective inquiry into Vietnamese language in the context of computational art by CodeSurfing and our fellows.

Revolving around the topic of monosyllabism, the project started with a research that dived into the grassroots of our language ― syllables, and observe the transition of our mother tongue into a monosyllable language and the emergence of unmeaning syllables in daily life. Built upon that initial research, the project later translated itself into four different artworks:

- [1] A Viet syllable keyboard.

- [2] An installation on the weight of syllables.

- [3] A social experiment on Viet-Muong phonetic similarity.

- [4] A performative system to let trees make poem.

Our Vietnamese Project has been exhibited at Vietnam's National Woman's Museum, awarded Best Popularity and Honorable Mention in Media Art of FutureTense Award 2025, and featured on Vietcetera, Thanh Nien and VnExpress.

🌒 The gigantic dataset of Vietnamese syllables

The Vietnamese language was born in the dense, misty forests that can disguise the Karst. From there, the language carried its Beloveds to the first capital and, with it, the expansion of the state. From the forest deep inland, the Vietnamese are now contemplating the vast ocean from endless sand dunes, turning the dangers in the grooves into cuisine and culture and blanketing the chilly imposing mountain ranges. Vietnamese has been going so far from its cradle. Today, Vietnamese is the star of the Austroasiatic linguistic family; it is the official language of a country that holds the sense of belonging of more than 100 million people. Changes did not just stay on maps, but also platforms. From inscribing on turtle shells and bones to marking time with stone, writing letters on paper, recording sounds, making phone calls, sending text messages, and posting status updates across the Internet. At this very moment, as we witness countless traditions either being granted wings to soar or absorbed into the modernity of the times, the Vietnamese language has long been present, quietly evolving and adapting, already there before we even noticed.

The ever-living Vietnamese language

“Between the mountain ridges and sea strands, bridging two major cultures of India and China, and survived the occupations of three powers: France, USA, and Japan. Trailing the technology from USSR, and went through script transformations, twice. Vietnamese now has its own flexibility to express every concepts, ideas, movements, and feelings that it has been through.”

The formation of the Vietnamese language has long been a topic of extensive research, comparison, discussion, and systematization by both domestic and international scholars. One cannot overlook the 16th-century An Nam Dịch Ngữ (Annamite Translation), which juxtaposed 716 Sino-Vietnamese words, or Alexander de Rhodes’ Vietnamese-Portuguese-Latin Dictionary, which formalized the use of the Quốc ngữ script (the modern Vietnamese script). The contributions of André-Georges Haudricourt, who explored the etymology of Vietnamese, should not be disregarded, particularly in his engagement with the work of Orientalist Henry Maspero to demonstrate that Vietnamese belongs to the Mon-Khmer branch of the Austroasiatic linguistic family.

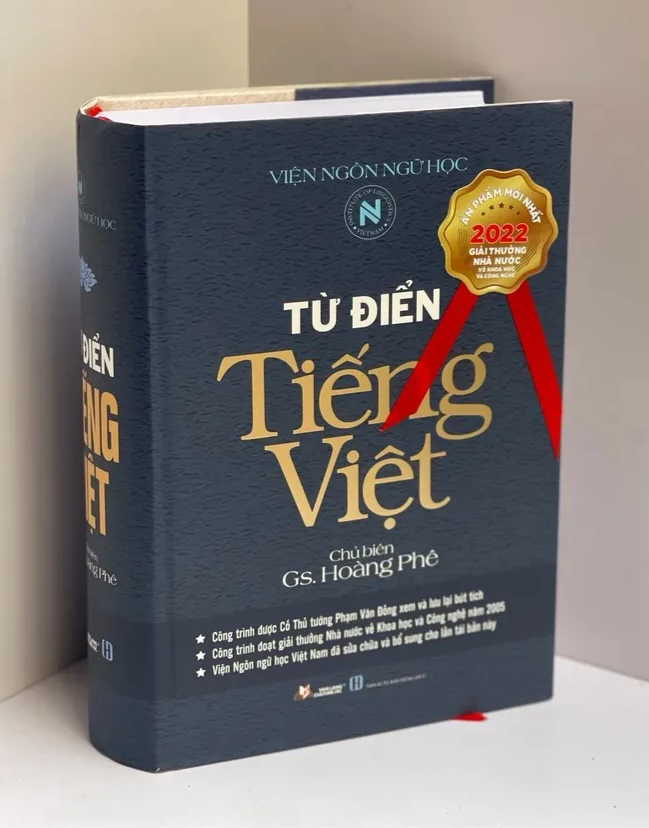

Similarly, the work of Professor Nguyễn Tài Cẩn on the tonal richness of Vietnamese, from its Austroasiatic origins—specifically the Mon-Khmer branch—to its adoption of tonal elements from the Tai-Kadai language family, is indispensable. Equally significant is the work of Professor Trần Trí Dõi, who meticulously systematized the development of Vietnamese within the broader cultural and historical contexts of turbulent eras. Today, the Vietnamese lexicon has been systematically organized thanks to the Vietnamese Dictionary by the late professor and lexicographer Hoàng Phê. Digital archives have also expanded into the realm of Chữ Nôm and languages within the Mon-Khmer group, such as the Vietnamese-Muong Dictionary edited by Nguyễn Văn Khang, the Katu vocabulary compiled by Nancy Costello, and the K'Ho-French Dictionary by Dournes Jacques, published in Saigon. There are numerous connections between Vietnamese and other languages, as well as between Vietnamese across different historical periods. However, to truly grasp the essence of the Vietnamese language, we must delve into its fundamental unit: the syllables.

Vietnamese in the sphere of poetic computation

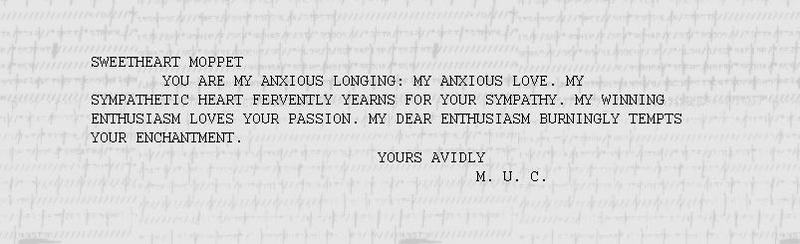

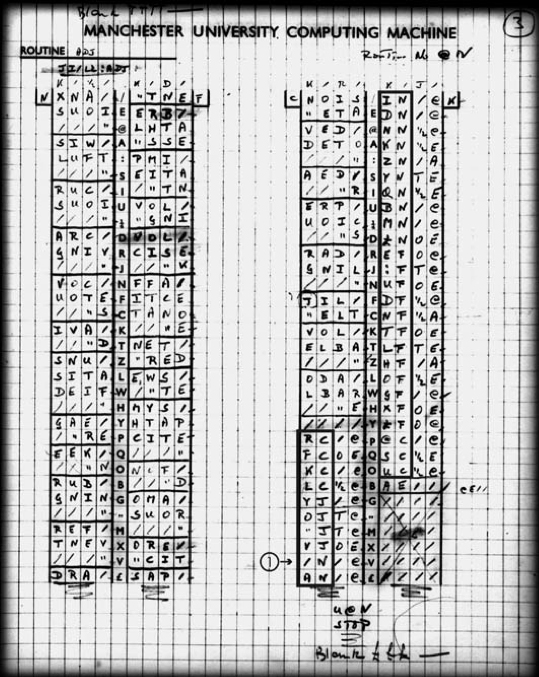

Since its very beginning, computation has always been poetic. In search for a queer history in computation, Rhizome mentioned about the love letter generator of Christopher Strachey as "the first example of algorithmic or computational art”.

“Each letter follows a similar structure, and is full of melodramatic Victorian overtones, with pet names like "honey," "jewel," and "moppet" along with other saccharine and yearnful descriptives. The letters were constructed via a generative algorithm that produced a variety of orders and combinations.”

The love letter generator is a playful way to look into poem and language in the sphere of computation. Subtle but passionate, it is considered to be a public display of affection between Christopher and Alan Turing amid the homophobic society.

“little record survives to document more than a passing relationship between these two men, but what remains is a surprisingly poetic attempt to play at the machine.” — Jacob Gaboury (Rhizome)

Upon this inspiration of poetic computation, we navigated our research into the poetic aspect of Vietnamese — how our language invokes its flexibility and intimacy. All cues lead to its syllables. Unlike English, Vietnamese is a monosyllable language. Every syllable in Vietnamese, when pronounced, invokes a certain feeling, a certain image. “đau”, “đớn” cut deep it bleeds. “trùng”, “điệp” embark on a great odyssey. That poetic must have come from our syllables.

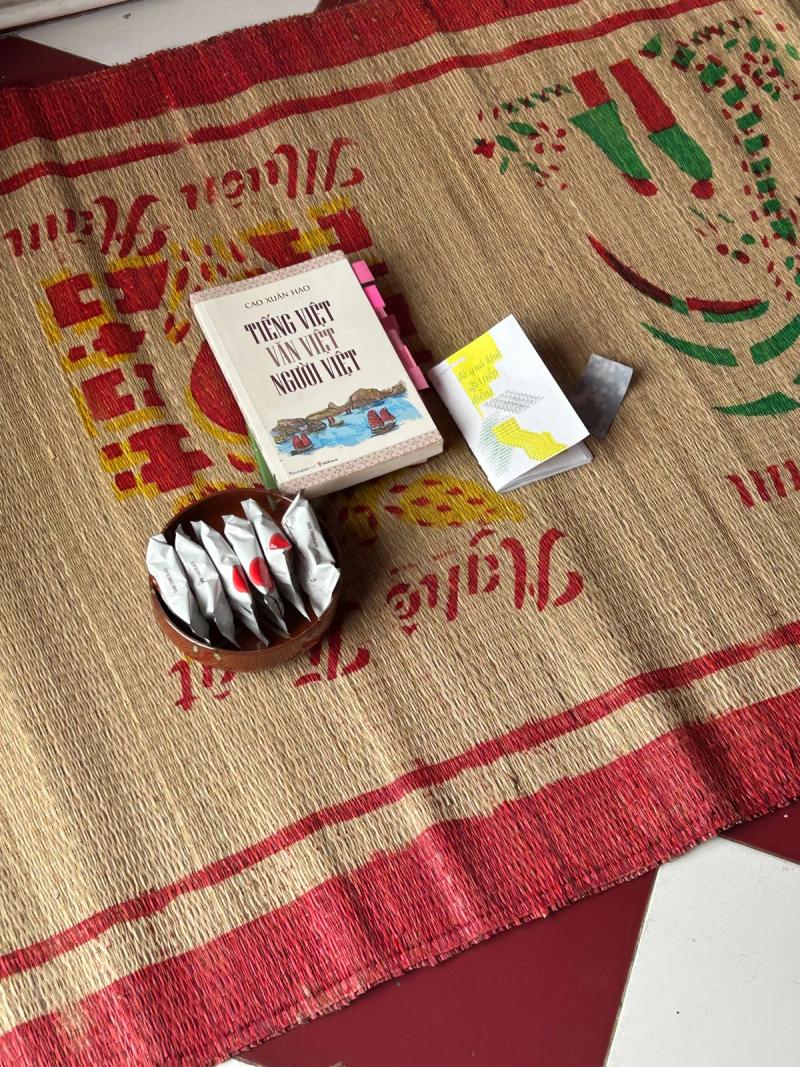

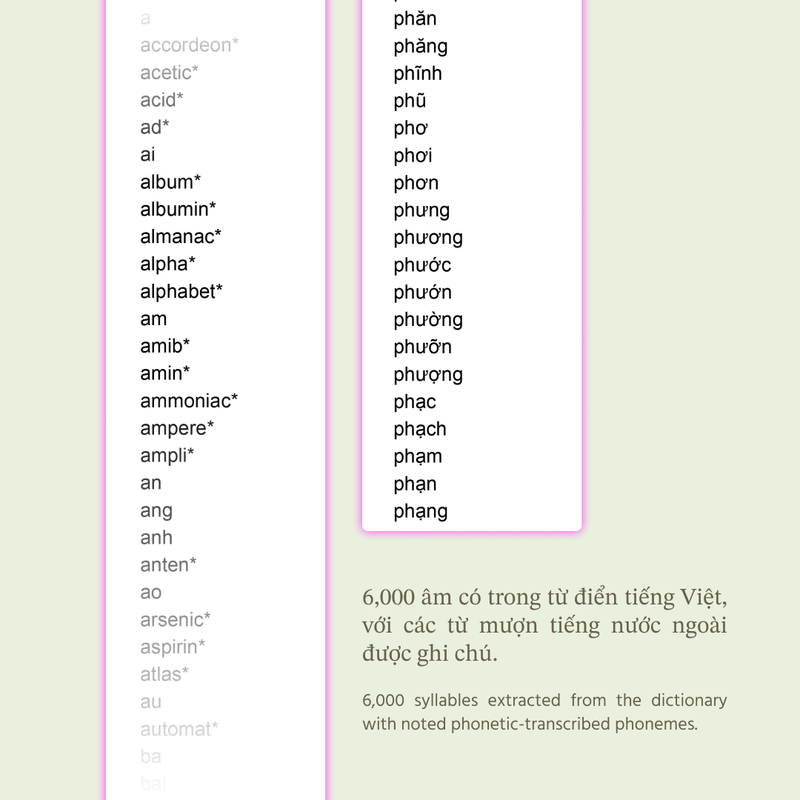

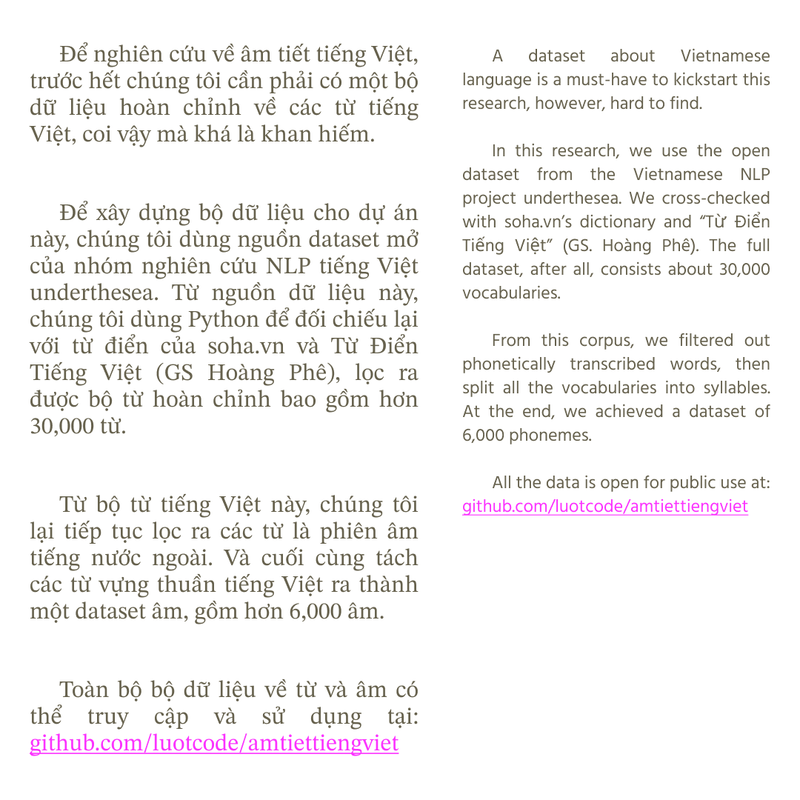

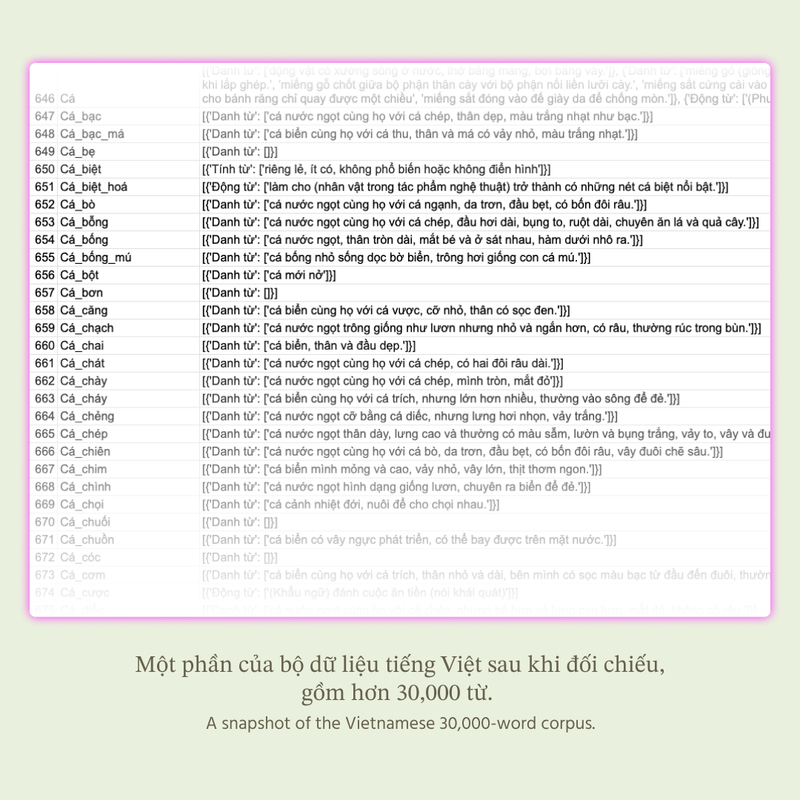

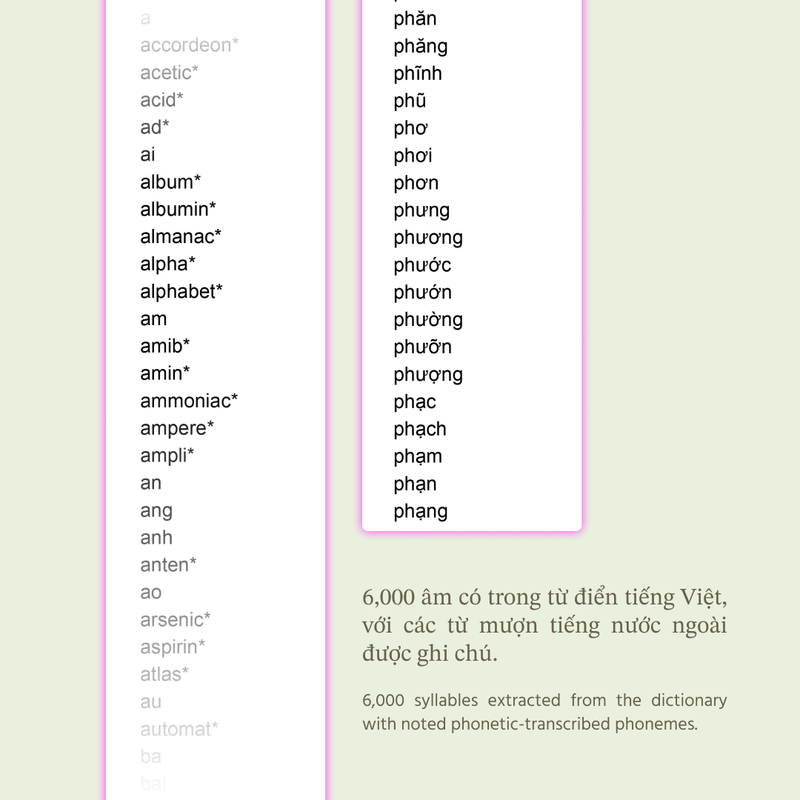

From that point, we delved into the syllables of Vietnamese. Upon the Vietnamese dictionary of Hoàng Phê, soha dictionary, and current NLP research of underthesea, we built a dataset of mono syllables of Vietnamese. While developing that, we published our observation in the format of 3 essays. This laid the foundation for our project and for Dmarc Lê, Đông-Trúc, and thou to extend their artistry into the poetic computation of Vietnamese.

[1] A Viet syllable keyboard

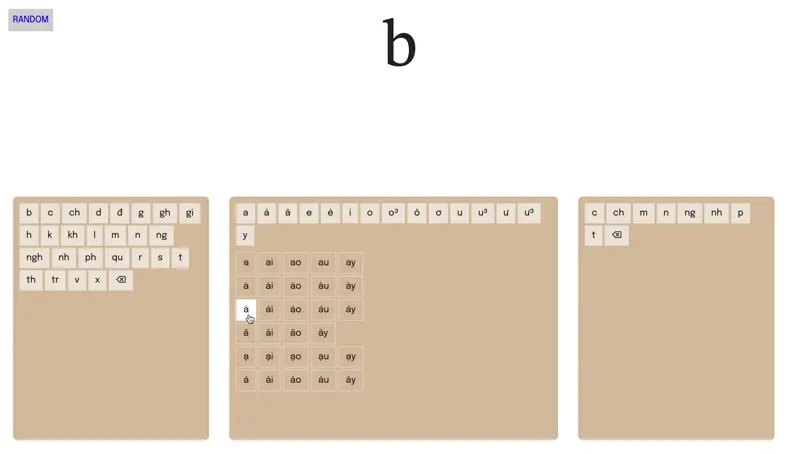

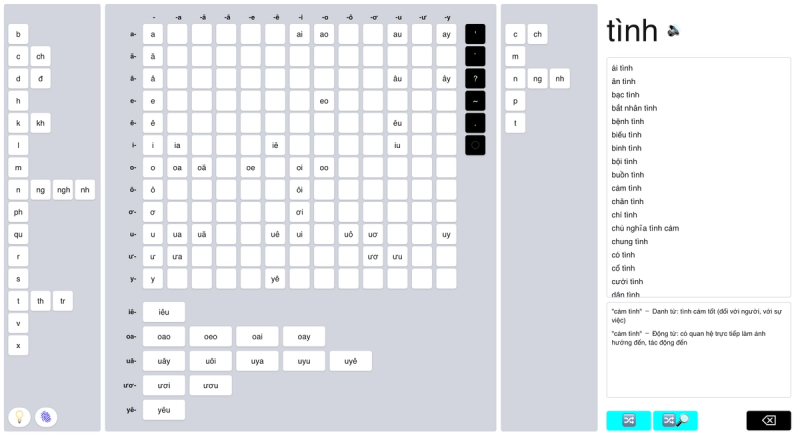

On that poetic observation about the Vietnamese syllables, the project started with a series of 3 researches, inquiring on the monosyllabism of Vietnamese. From this research trilogy, an attempt is made to redesign the Vietnamese keyboard, structuring it by syllables rather than individual letters.

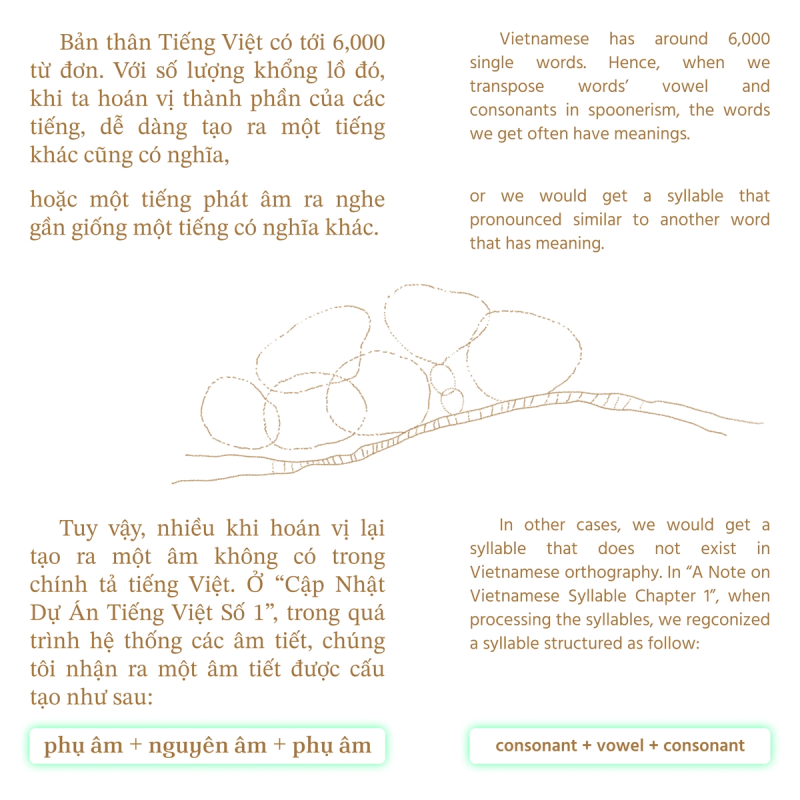

The foundation of the research draws from three primary sources: the digital dictionary from soha.vn, the 2021 edition of Từ điển Tiếng Việt edited by Hoàng Phê, and an open-source Vietnamese NLP dataset by the underthesea research group. From these sources, we processed, cross-referenced, and systematized 6,000 unique Vietnamese monosyllables that has meaning in dictionaries.

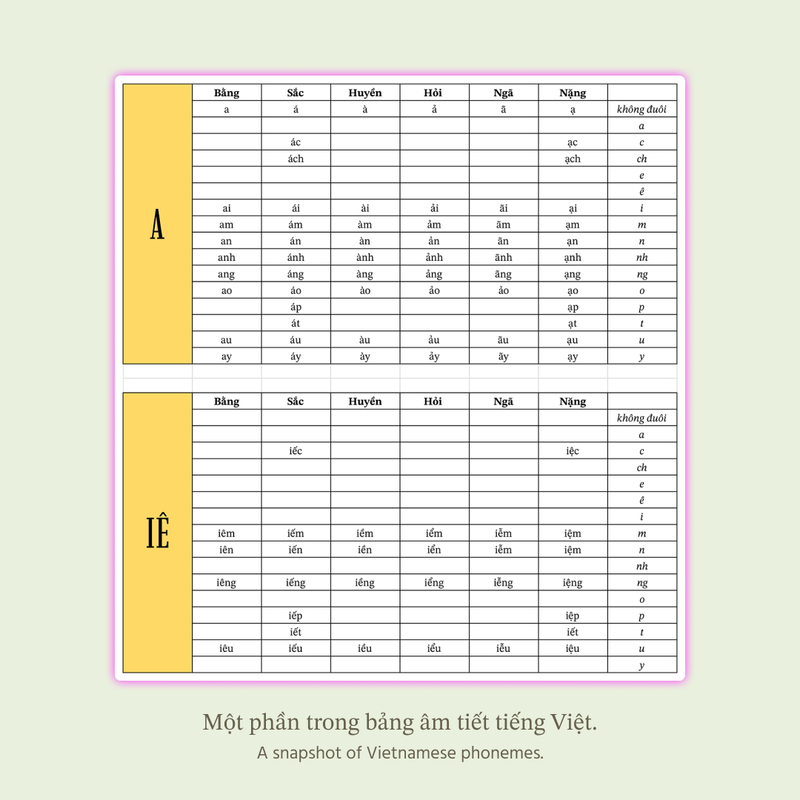

We notice that Vietnamese syllables are following the structure:

initial consonants (optional) + vowels + final consonants (optional)

Examples:

bánh = b + á + nh

cá = c + á + _

êm = _ + ê + m

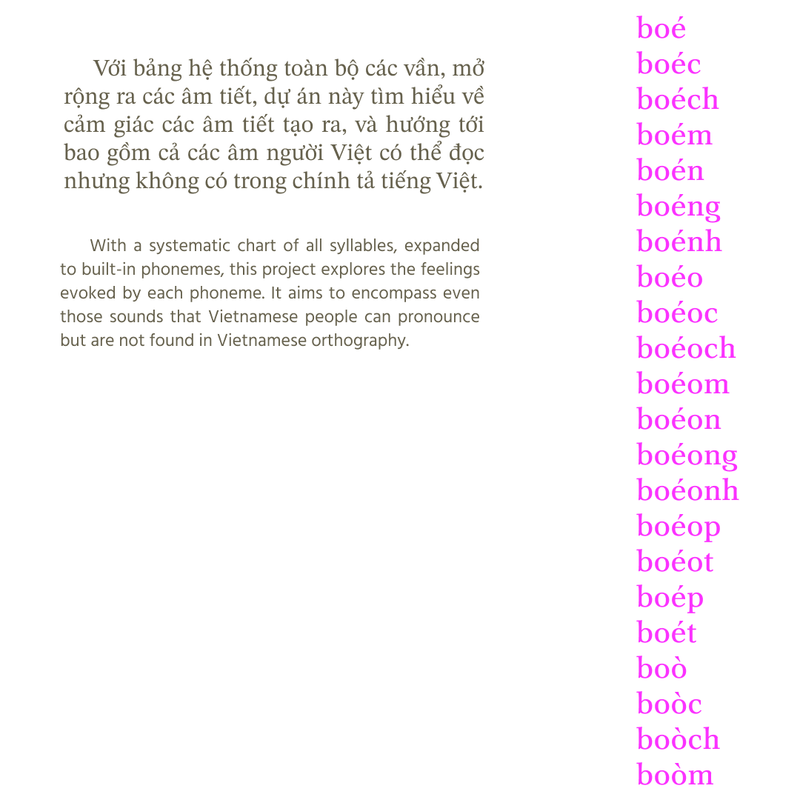

To understand the mechanics of syllable formation, we broke all the syllables down into these three core phonetic components. Then, algorithmically recombining these elements, we generated a dataset of 82,000 possible syllables, including both the 6,000 commonly used ones and 76,000 novel (for examples: "boéch", "gập", ... ) yet phonetically plausible syllables. These "unfamiliar" forms invite a renewed awareness of Vietnamese phonology.

These newly discovered syllables are documented at our Github, together with its open source code. To help expand the project, we created a new Vietnamese keyboard ⎯ one that based upon the syllabic components of Vietnamese, rather than the normal QWERTY keyboard that centered around the alphabet.

The original version of the keyboard

Updated version. A physical version is in the making.

Typing is a key interaction between us and computer. Typing is a way of using language. Users forming the words in the mind and put them into life by physically pressing on keys. Typing reflects how we use language to rationale and navigate in digital era.

The result is a prototype keyboard designed not just as a practical tool to support the research on Vietnamese syllables, but also as a medium for exploring the latent richness and creative potential of Vietnamese syllables.

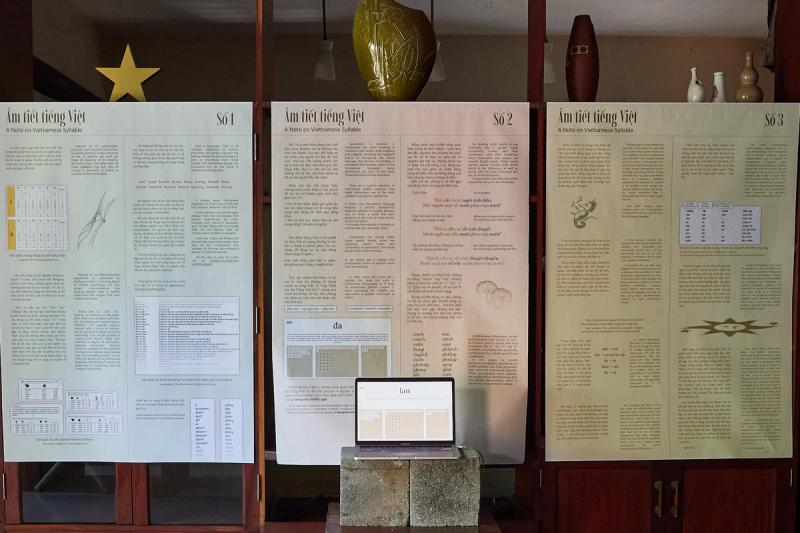

Continued on that, we looked deeper into the monosyllabism of Vietnamese, reflecting on spoonerism and the phonetic change from time to time. The entire research was published in 3 episodes.

Ep.1: A note on Vietnamese syllable

Overview of Vietnamese Syllables and the creation of an Open Syllable Database for the community. This project compiles all possible phonemes in the Vietnamese language and cross-references them with dictionaries, analyzing how many of these sounds carry meaning and how many are nonsensical.

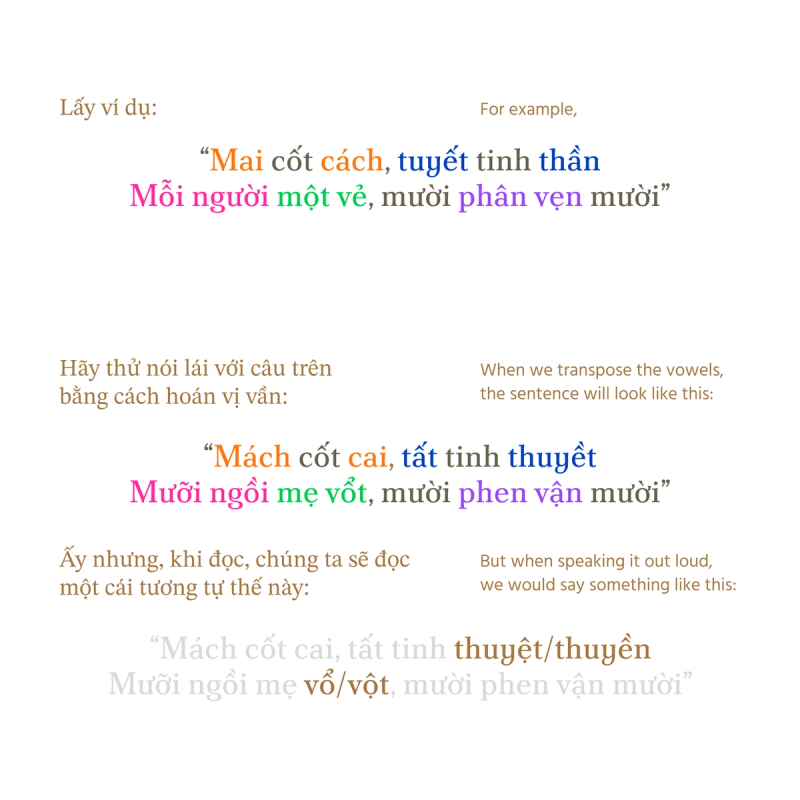

Ep 2: Spoonerism and The "Dark Side" of Vietnamese Syllables

How Vietnamese’s monosyllabism facilitates the most common word play in daily life: spoonerism. In Vietnamese spoonerism, the speakers can adjust the nonsensical syllables into one with meaning.

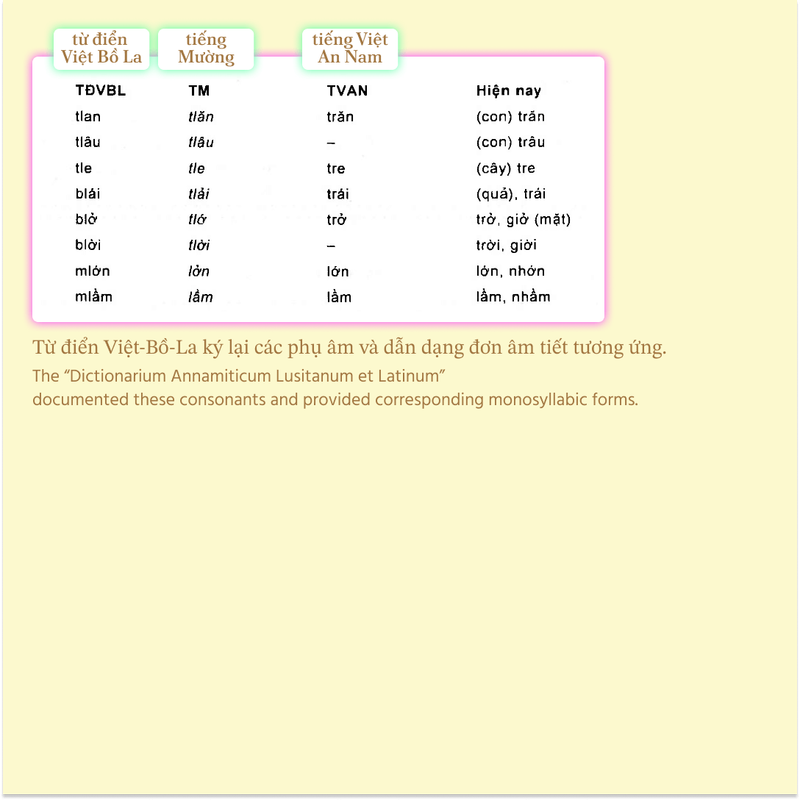

Ep 3: The Aging of My Mother Tongue

An observation of the shift into monosyllabism of the Vietnamese language through documents and records on consonant clusters and pronunciation in Middle Vietnamese.

🌓 Extension into a fellowship

With the open dataset of 82,000 syllables, in June 2024, CodeSurfing introduced Our Vietnamese Project to the community, calling for collaborations with local artists and language enthusiasts. By combining linguistic research with artistic experimentation, the fellowship expects to continue the ongoing research, which is centered around Vietanamese's monosyllables while opening up new, imaginative ways of engaging with the language.

Through open call, we found three emerging artists—Dmarc Lê, Đông Trúc, and thou. Though their practices vary, all three found a shared curiosity in the Vietnamese syllables. Their works reflect a continued exploration of how monosyllabism can shape meaning, sound, rhythm, and identity in both conventional and experimental contexts.

[2] Xác Âm (Dmarc Lê)

Dmarc Lê is a digital designer with a passion for exploring the world. Born and raised in the old citadel of Vietnam, she now finds her playground in the digital space, where she studies and experiments with the connection between machines and humans.

Email: dmarcle.hi@gmail.com

Instagram: @dmarc.le

Website: dmarcle.com

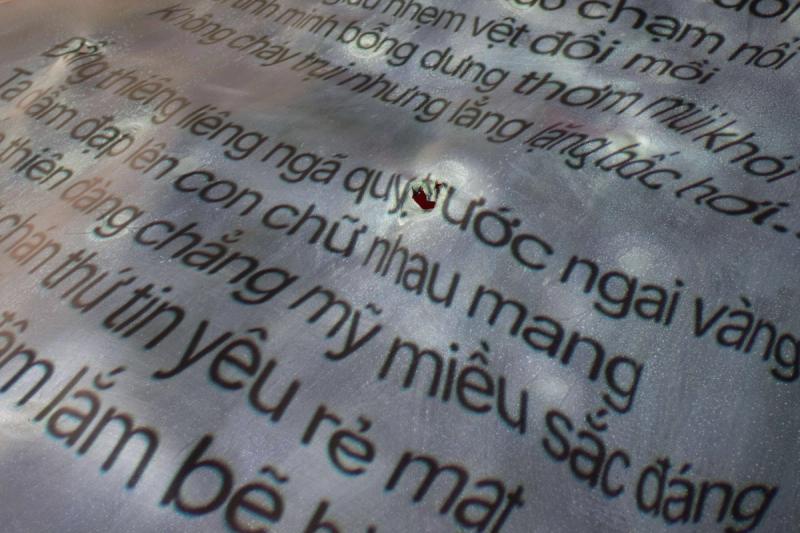

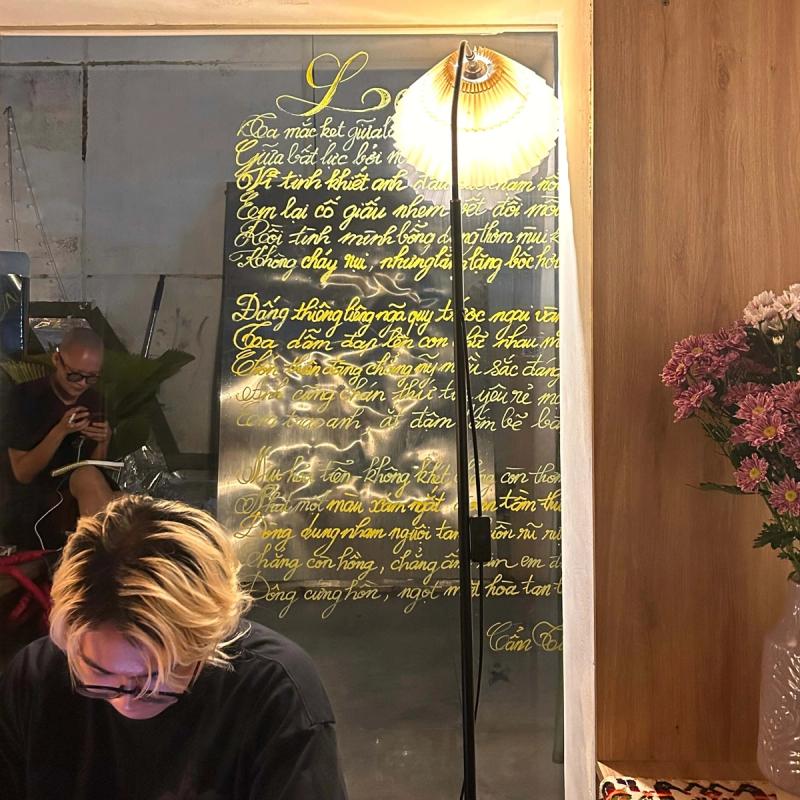

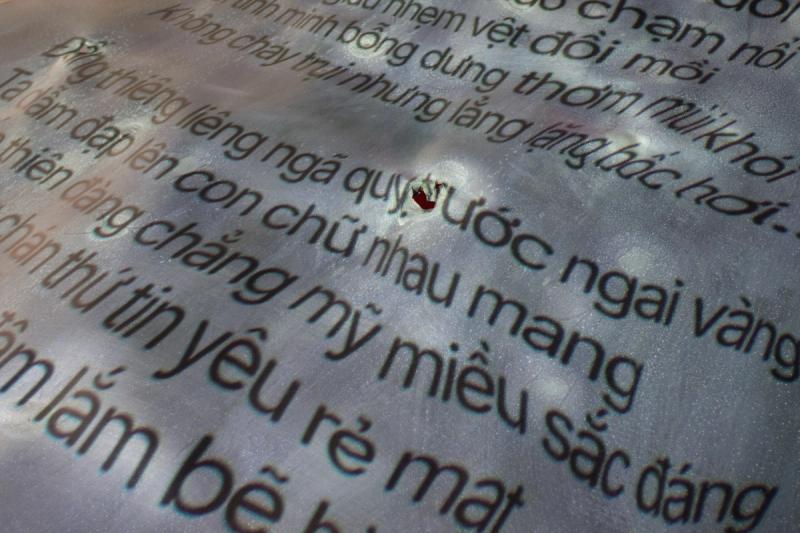

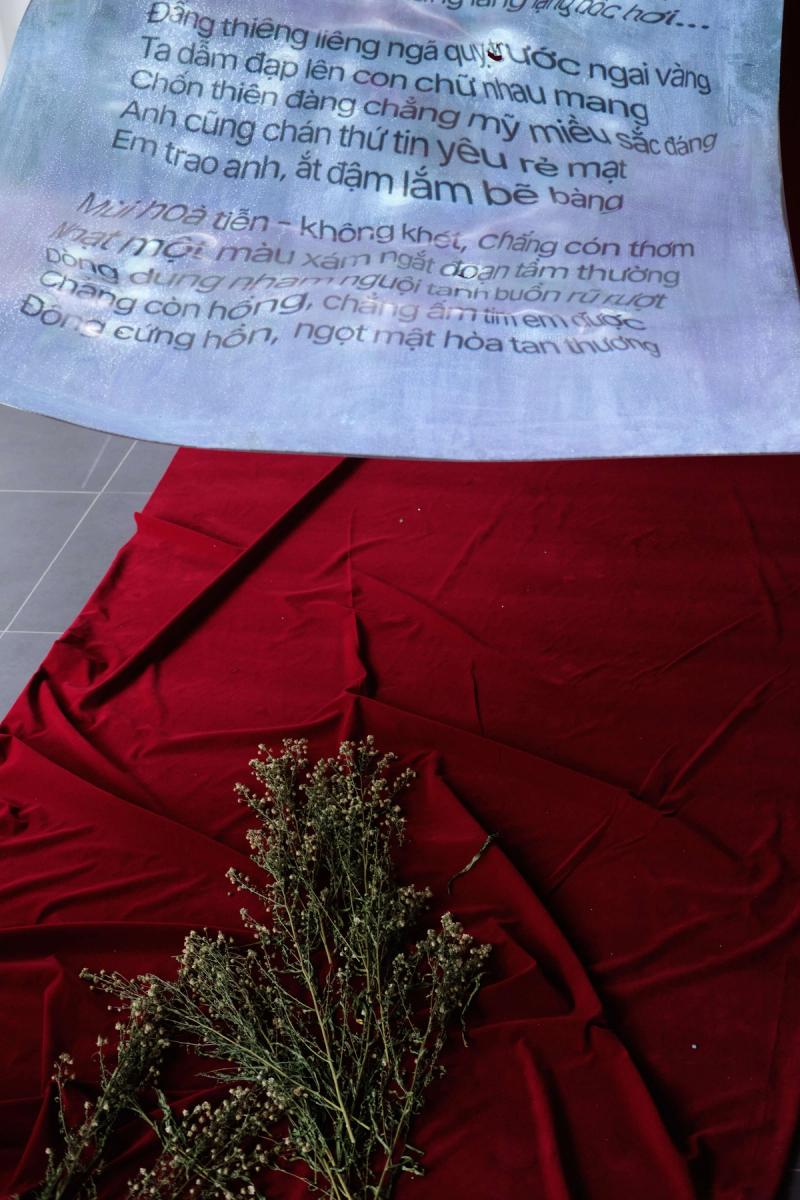

“Xác Âm - A left body of word” takes shape from a metaphysical question: Where does a poem's weight reside? Each syllable in Lạc, a free-verse poem by Cẩm Tiên, was “weighed in” through the ASJP system. Its approach is to categorize vowels and consonants based on the movements and placements of teeth, lips, and larynx when we pronounce words.

The artist deepens this process by layering in her own tongue, a native of Huế, mapping a matrix where syllables’ weight were translated into scores. The juxtaposition of high and low scores were etched onto metal. The higher the score is, the longer it has to endure the blowtorch’s heat.

Once cooled, the poem was exposed to the monsoon elements, its form eroded by time, weather, and decay. Xác Âm captures a fleeting moment in the ever-changing life of Vietnamese syllables; a meditation on the delicate interplay between text, sound, and emotional pulse.

— The poem *Lạc* by *Lê Minh Cẩm Tiên*

Ta mắc kẹt giữa lằn ranh sáng tối

Giữa bất lực bởi nỗi phải chia đôi

Vì tinh khiết anh đâu nào chạm nổi

Em lại cố giấu nhẹm vệt đồi mồi

Rồi tình mình bỗng dưng thơm mùi khói

Không cháy rụi nhưng lẳng lặng bốc hơi…

Đấng thiêng liêng ngã quỵ trước ngai vàng

Ta dẫm đạp lên con chữ nhau mang

Chốn thiên đàng chẳng mỹ miều sắc đáng

Anh cũng chán thứ tin yêu rẻ mạt

Em trao anh, ắt đậm lắm bẽ bàng

Mùi hoả tiễn - không khét, chẳng còn thơm

Nhạt một màu xám ngắt đoạn tầm thường

Dòng dung nham nguội tanh buồn rũ rượi

Chẳng còn hồng, chẳng ấm tim em được

Động cứng hồn, ngọt mật hoà tan thương

A brief Q&A with Dmarc Lê

Q: Every syllable we utter requires energy, and our pronunciation adapts to natural and geographical conditions. For instance, peoples living in steppes tend to use more vowels and resonant sounds, while those in forests use more fricatives and consonants. What are your thoughts about your own accent?

A: The melodic quality of the Hue accent likely stems from its poetic landscape - the Perfume River & Ngu Mountain. The people of Hue are deeply enchanted by their natural surroundings, which has undoubtedly influenced their speech patterns. The Hue accent is gentle and pleasant, flowing like the Perfume River as it meanders through the city's corners. However, in everyday speech, this gentleness carries a certain decisiveness, sometimes becoming quick and gliding across the tongue - perhaps influenced by the Ngu Mountain range. Interestingly, the Hue accent doesn't reflect the harsh local weather; perhaps we're too romantic and naturally gravitate toward the poetic.

Q: What do you think is the difference between a prose sentence and a line of poetry?

A: A prose sentence is part of a story. A line of poetry is a story in itself.

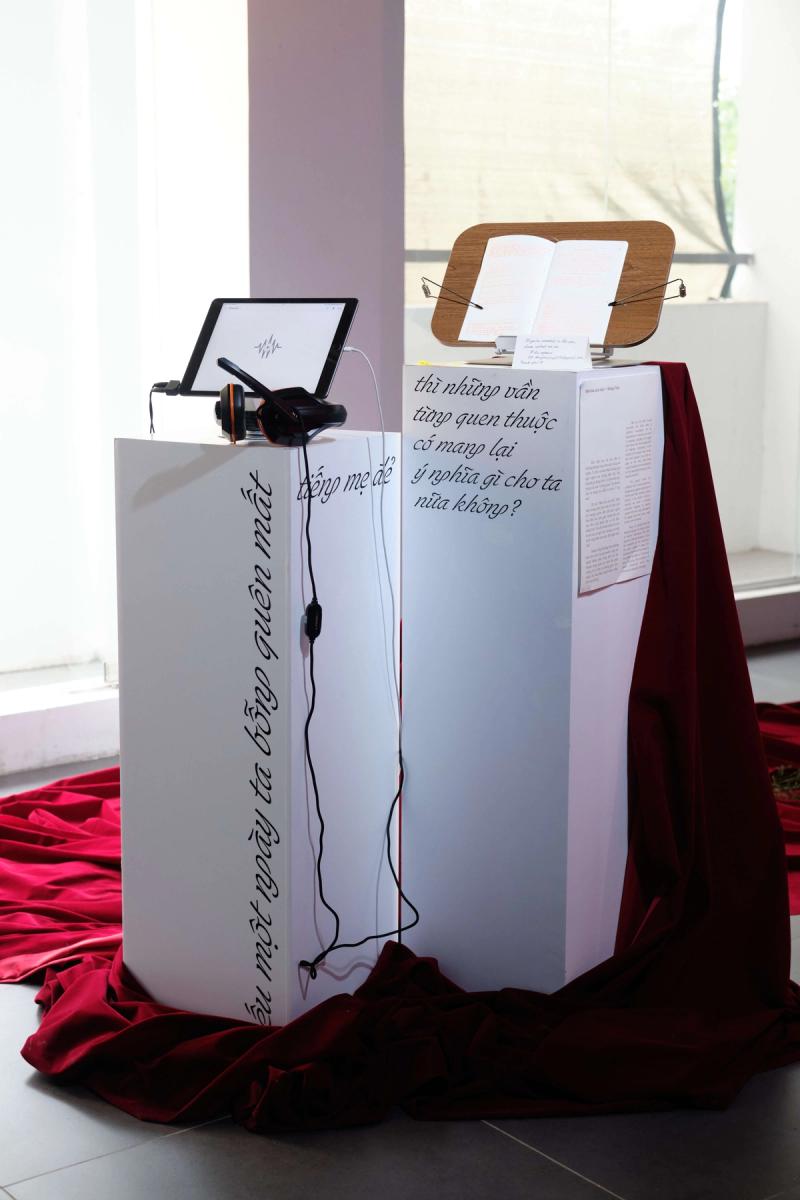

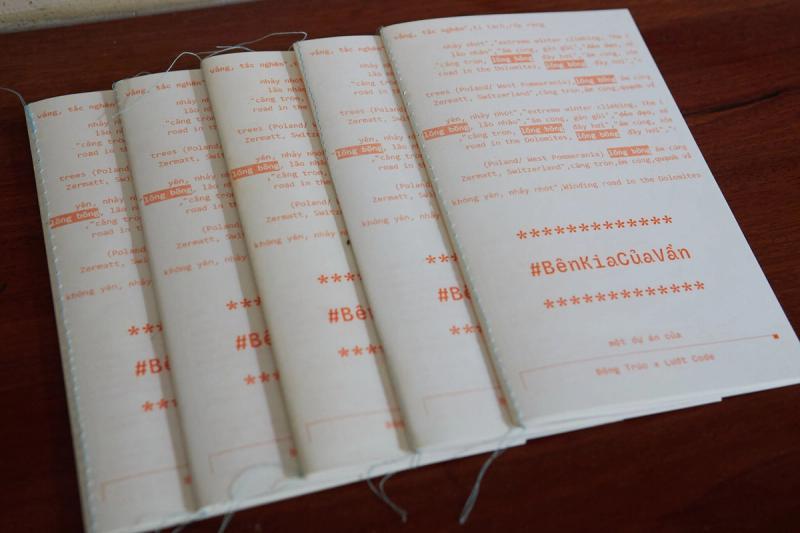

[3] Bên kia của vần (Đông-Trúc)

Đông-Trúc is a typographic designer. Growing up exposed to different accents and cultures from the North to the South of Vietnam nurtured her sensitivity and curiosity toward the Vietnamese language, becoming the driving force behind her practice.

Email: dongtrucng2810@gmail.com

Instagram: @do_ngtruc

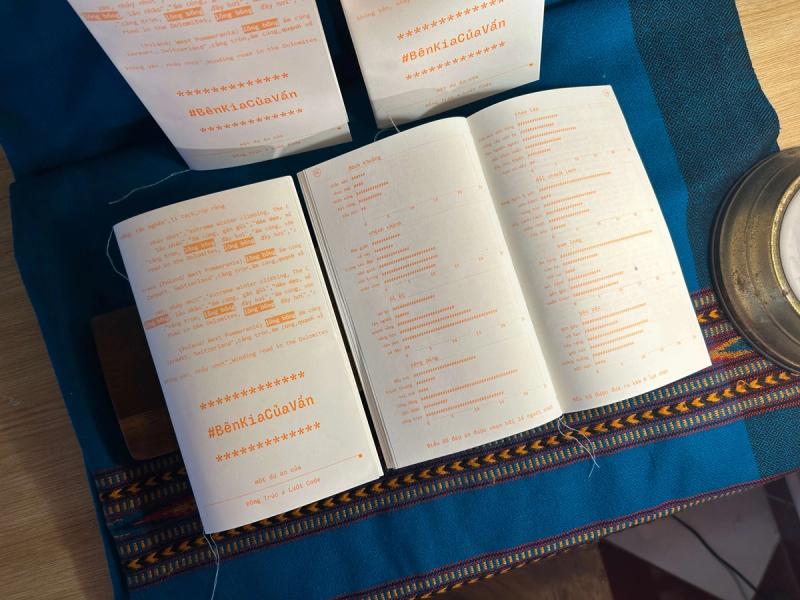

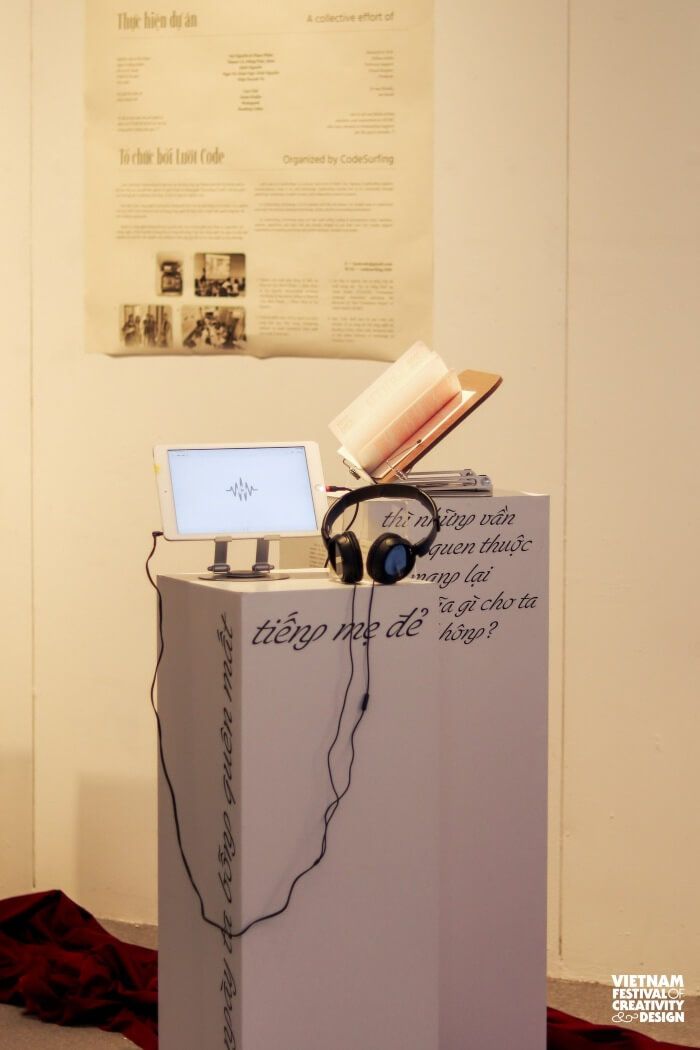

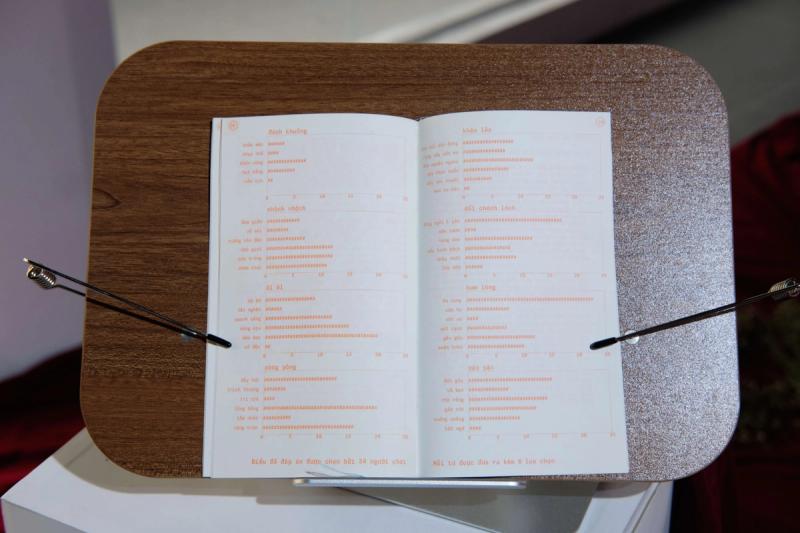

“Bên Kia Của Vần” (loosely translated: The Other Side of Syllables) investigates the co-dependence of meaning and sound in language. Typically, we engage with rhyme from the vantage point of meaning, interpreting words through the concepts they convey. But what happens if we shift our gaze to the other side—where sound, liberated from the necessity to hold designated meaning, holds expressive power?

This project invites the audience into a social experiment, designed as a playful exploration of rhymes and their auditory impact. Rooted in the artist's curiosity—whether we share a universal emotional response to specific sounds—the work asks participants to engage with the purest, most sensory form of rhymes.

Đông-Trúc decided that the Mường language, the kinest cousin of modern Vietnamese that had been her childhood neighbor, to be the treatment for this discourse. The artist created a space for audiences to immerse themselves in the auditory qualities of rhyme and tone, exploring the possibility of shared resonances within the Vietnamese linguistic landscape.

A brief Q&A with Đông-Trúc

Q: What sound or word evokes images and memories of Di Linh for you?

A: "Lênh đênh" (adrift). It might sound strange to use this word to describe a highland region! But that's how I feel when I think about Di Linh, which I consider my first hometown where I grew up. My second hometown is in a coastal area of Central Vietnam, where I was born, where my grandparents and relatives live, and where I spent joyful summer holidays. As a child, my parents would often take me back to visit. The constant movement between these two places gave me a feeling of being adrift. I felt like I was floating between them, not truly belonging to either place.

Q: What are your thoughts on the Muong language (pronunciation, vocabulary, writing system) while working on this piece?

A: Working on this project and interacting with the Muong language has been a journey of constant surprises. Initially, I was struck by how closely related it is to Vietnamese. While listening to Muong news broadcasts, questions began to emerge - questions that were also raised by some visitors - about whether ethnic minorities have their own writing systems. Do Muong people actually use the Latin alphabet to write their language? When a language lacks a writing system, can it continue to develop? And how does it evolve without the tools for documentation?

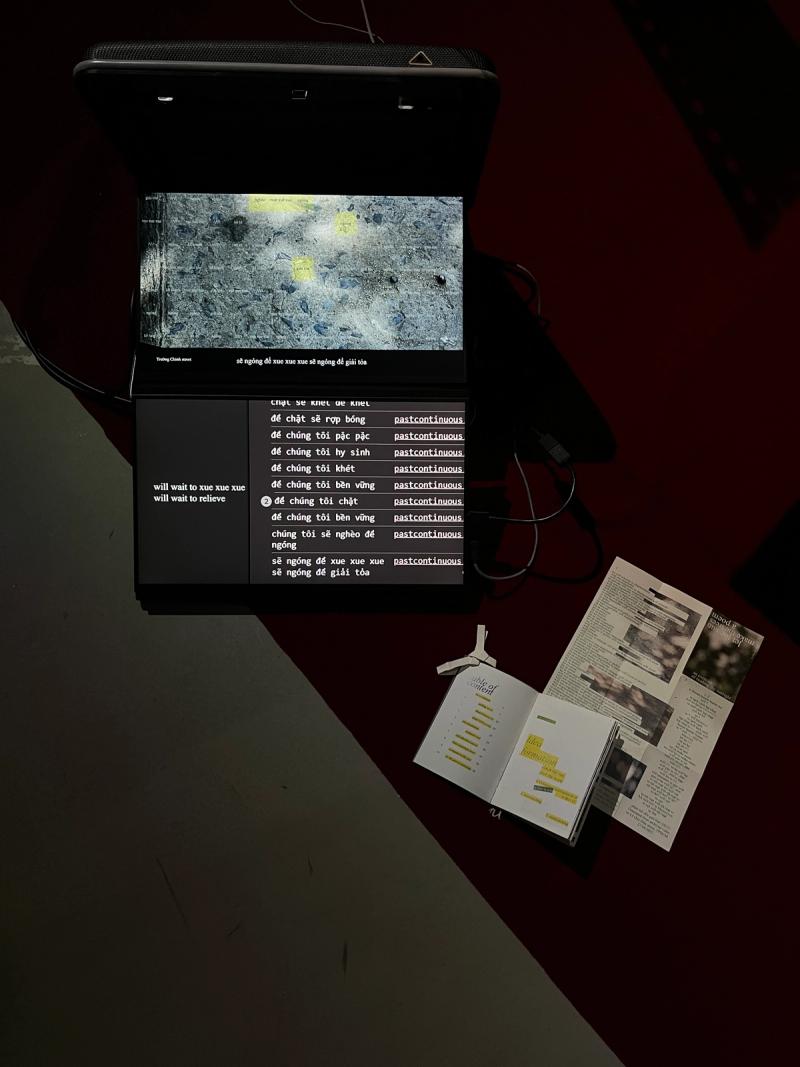

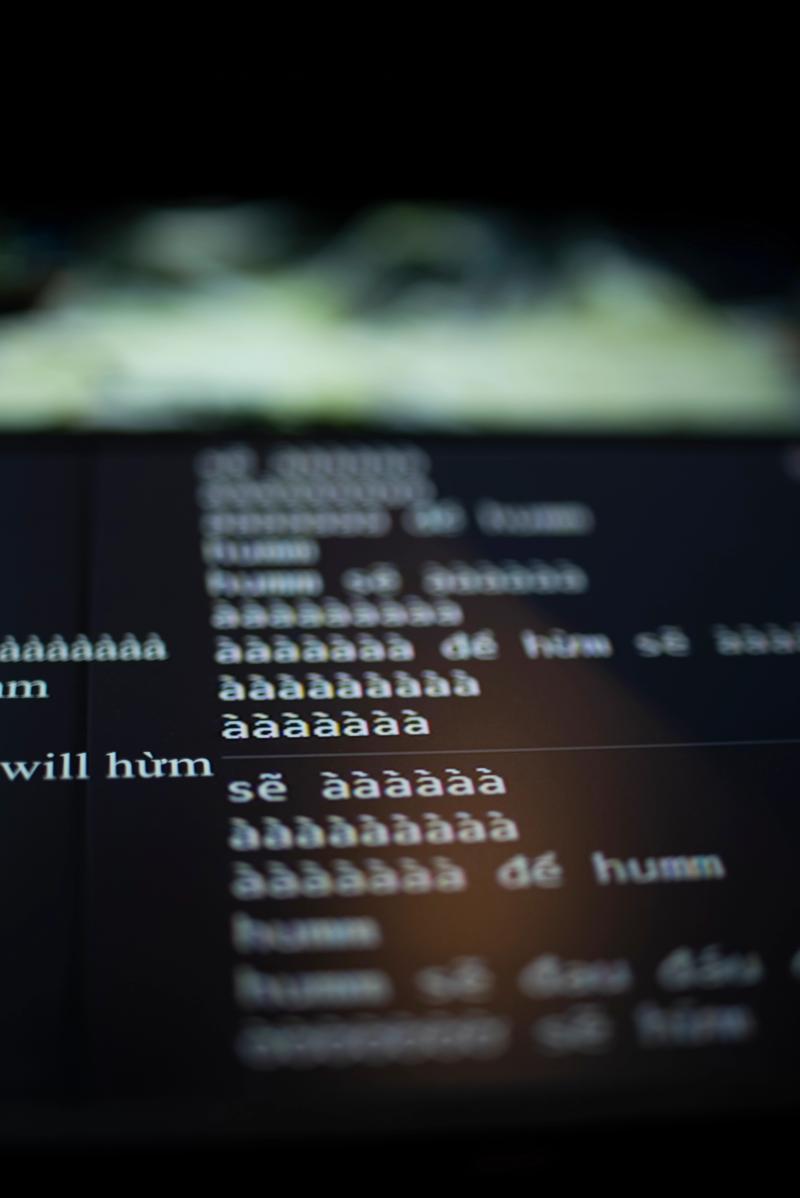

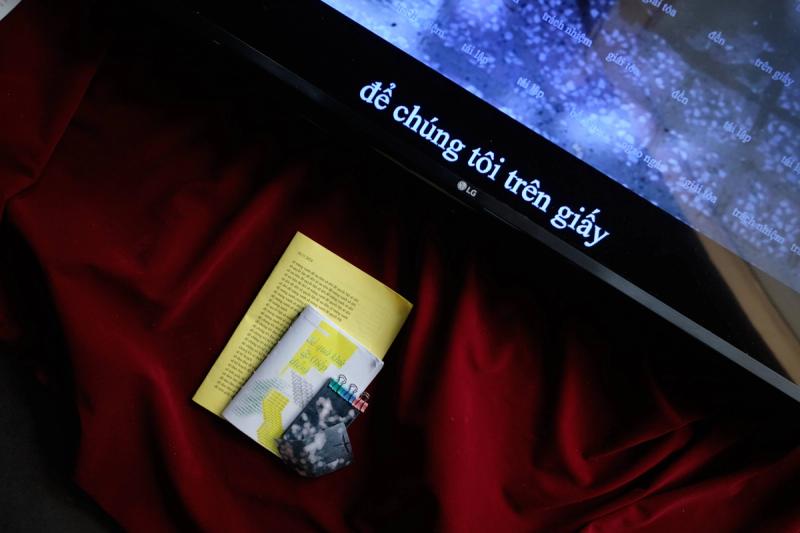

[4] để quá khứ sẽ (tiếp diễn) (thou & Khôi Nguyễn)

Try "bắt nắng" tool

Read about behind the scene

thou is a creative practitioner living in Ho Chi Minh City. Their practice using multi-medium focusing on visual (illustration, photography, installation) and creative text. thou's exploration topics are rooted to local culture, and revolve around their existence, questioning their connections with the surroundings, especially in space and time.

Email: tuchury@gmail.com

Instagram: @thou.____________.thou

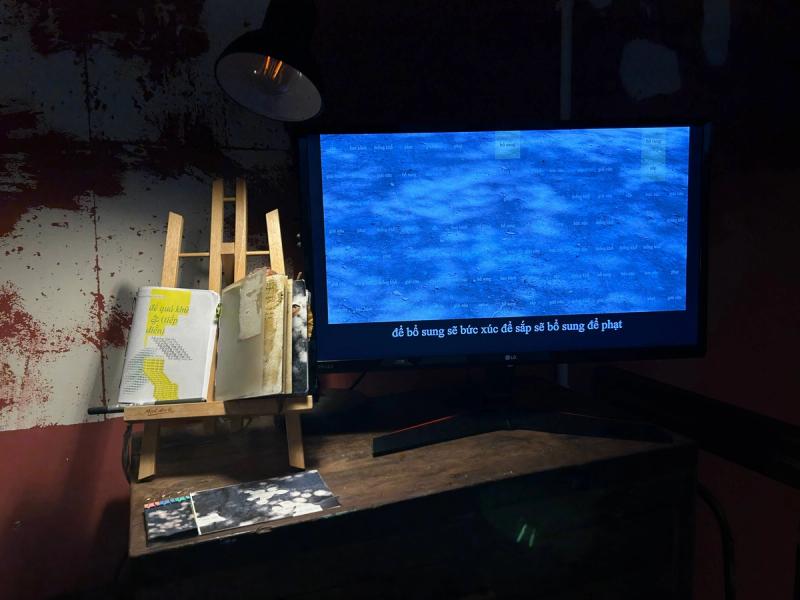

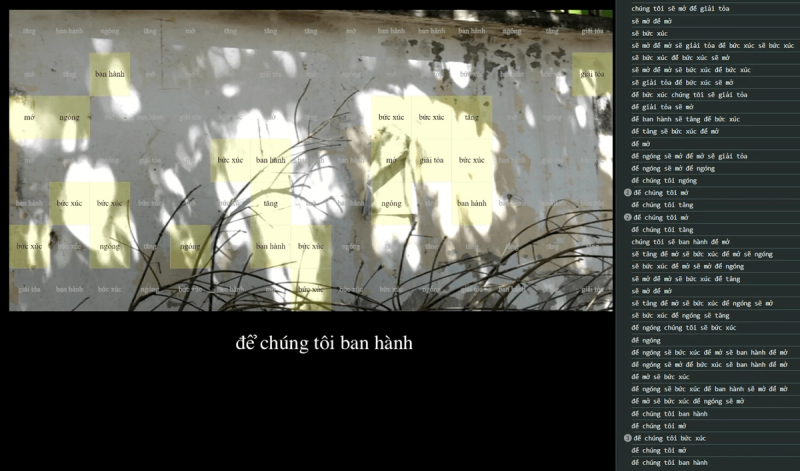

để quá khứ sẽ (tiếp diễn) (loosely translated: for the past will (continue)) delves into the layered intersections of memory, language, and urban landscapes. Through an autogenerated poetry mechanism, shadows of trees cast on walls by sunlight serve as a metaphor for the way the past unfolds and lingers in the present. This work is a manifestation of tree’s “freedom of speech’; it allows the trees to

utter the things they cannot talk, about

the tree lines that had fallen, for

the bridges and pillars to come, about

the scorching misery that bestowed, upon

the denuded solitude that casted its shadow, over

the trees enlisted to be chopped, off

the promises to re-plant, at

the promises that decaying on paper, about

the continuation of the past continuous.

Drawing from over 50 news articles about Metro Line No. 2, the artist selects 49 key words and phrases, constructing a lexicon of the trees. These words are inserted into a repetitive syntax—"để...sẽ...để...sẽ..." (to…[we] will…to…will) —that loops endlessly, pushing language to its breaking point, where meaning dissolves into oblivion and promises become empty shells.

The work is a poetic confrontation between technology and nature, randomness and structure, where sunlit shadows evoke the violent history of urban deforestation. It highlights the tension between the natural world and the relentless forward march of urbanization, exposing the fragility of both memory and language in the process.

A brief Q&A with thou

Q: What's a "will...to..." or "to...will..." phrase that you often use?

A: The phrases I use most often are promises made to my mother during arguments, like "I will [abc] later" where "abc" could be any reason she's scolding me. For example, "I will hang the laundry later," "I will do it later," or "I will be more mindful." These phrases work well when the "abc" action can be immediately verified. However, when these "abc" actions are set in a distant future that neither my mother nor I can predict, and when we don't know if the mistakes will be repeated, these phrases often bounce back with my mother's question: "Why is it always 'will'? When will 'now' come?"

Q: How do you think the past continuous tense manifests in Vietnamese?

A: An interesting aspect of Vietnamese is that it doesn't have tenses like English does. Words like "đã, đang, sẽ" don't strictly define past, present, or future, but rather express the aspect of the verb. The past meaning of a phrase or sentence emerges indirectly from the entire structure and elements within the sentence, rather than directly from a single word. While reading articles about urban trees, I looked back at pieces from over 10 years ago - technically in the past relative to now. However, these articles share a common pattern of repeating the word "will," which made me think deeply about the ambiguity between past and future, how when promises remain unfulfilled, the past continues to repeat itself. Therefore, even when reading articles in the present moment, I still see the same old issues, worn-out phrases, and meaningless sounds. The "past continuous tense" in Vietnamese manifests through the repetition of information we already knew before, with words serving merely as formal announcements.

🌓 ⎯ The legacy lives on

⎯ Trần Thị Minh Giới, Vietnamese Linguistic Researcher

This exhibition highlighted one key idea: that Vietnamese is a living language—one that constantly evolves alongside changes in life and society. With over 40 years of experience teaching Vietnamese to native speakers, people of Vietnamese descent, and foreigners, the teachers observed that exploring the language through this lens can spark inspiration and enthusiasm in learners. In addition, the data collected and analyzed by Lướt Code provides valuable insights for educators and linguists alike, offering new perspectives for their research.

⎯ Tammy, Managing Editor at Vietcetera Media

On Saturday morning, I gave up sleeping in to visit the Vietnamese Language Project by Lướt Code. Lướt Code is quite an eccentric creative collective that might make you a little wary when you first meet them. Don’t worry—they’re actually very sweet. This community was founded with the hope of integrating technology into artistic creation, so that technology no longer feels like something distant or unreachable. In this project, they use coding to play with the Vietnamese language. I came across three artists—Dmarc, Trúc, and thou—with three works:

- Making the weight of a poem tangible by blowtorching a metal sheet; the heavier the syllable (according to the ASJP system), the longer it is torched.

- A sound perception game with the Mường language that records the meaning guesses of over 30 players.

- A sun-catching poetry device that measures sunlight intensity to select words for a poem.

“What’s the point of making all this stuff, really?” I turned and asked Nhân, the founder of Lướt Code.

“It’s a source of inspiration for artists to create something from technology. Because in the end, technology is just a medium—it’s up to people to connect things together. Like bringing sunlight and poetry closer to each other,” he explained.

That same day, I learned about the concept of creative coding.

⎯ Sherry Nguyễn, PhD Candidate at Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University.

To be honest, I’ve never been particularly good with words or literature. And in the past, since I thought of myself as Vietnamese and Vietnamese as my mother tongue, I neglected to really nurture it—focusing instead on learning other languages. But in the past year or two, especially after hearing Yui talk about the Vietnamese Language Project, I’ve come to realize that Vietnamese is far more beautiful and unique than I’d thought. The exhibition on September 28 really affirmed that. It enlightened me about the roots of the Vietnamese language and helped me see that Vietnamese is truly something special, haha. The atmosphere of the exhibition felt very Vietnamese, which matched the theme perfectly. They also played 432Hz frequency music, which was incredibly soothing—it made me want to just sit there, look at the trees and sky, and reflect on everything I had just read and seen. I really appreciated the way the artists combined language with art, technology, culture, and social issues. It made me realize how deeply language is connected to the cultural and historical context of a country.

🌓 ⎯ The team

- Author ⎯ Phan Nhân & Yui Nguyễn

- Artist ⎯ Dmarc Lê, Đông-Trúc, thou, Khôi Nguyễn

- Producer ⎯ Nhat Huynh-Vu

- Technical support ⎯ Quang Anh

- Visual designer ⎯ Ngọc Võ, Hani Ngô

To our friends, we thank

- Lưu Chữ for supporting us in steering the project from the very beginning.

- 3năm Studio for providing the space and time to bring this project to life.

- WEDOGOOD for going above and beyond to assist Trúc with her publishing.